Change in the European ACMI landscape?

Are North American-style capacity purchase agreements taking off in Europe and what effect could these have on leasing regional aircraft? Angus von Schoenberg, Industry Officer of TrueNoord examines this growing trend

Among Europe’s regional airlines, an emerging trend over 2017 was the transformation of some business models into wet-lease capacity providers.

The announcement at Farnborough Airshow 2018 that Air Nostrum and CityJet are combining forces could profoundly affect the regional aviation landscape in Europe over the coming years. This

combination creates Europe’s largest ACMI (aircraft, crew, maintenance and insurance) capacity provider; however, questions remain about whether more of Europe’s legacy national carriers will buy into this model.

The US market is dominated by a small number of independent mega-regionals, Mesa (145 aircraft); Endeavor (146); and Republic (189) and dwarfed by Skywest (447). All of these operate services on behalf of at least two large US legacy carriers, except Endeavor which flies exclusively for Delta. In Canada, Jazz (116) and Sky Regional (25) operate as Air Canada Express. All of these carriers provide aircraft on so-called capacity purchase agreements (CPA). These are longterm ACMI contracts that typically last for about ten years and are often extended thereafter. The scale and long-term stability of these carriers enables legacy airlines to have sufficient confidence to provide long-term contracts for large fleets of regional aircraft which, in turn, allows the regionals to acquire and finance their aircraft on economically attractive terms.

Current European model

To date, the European landscape has been much more fragmented with a few large carriers including Lufthansa Cityline, KLM Cityhopper and HO P!. However, these are wholly-owned subsidiaries of major European airlines that operate almost exclusively on each carrier’s behalf, they generally do not provide ACMI capacity. In the past, Europe’s ACMI landscape was dominated by smaller carriers such as Danish Air Transport (15), Adria (17) and WDL (5) which provide shorter term and often ad hoc capacity. Their smaller scale and, often, non-unionised crews mean that longer contracts have been resisted by the pilot unions at major carriers so that those needing ACMI capacity have been unwilling to, or even blocked from, agreeing to longer-term contracts with such independent providers. This means that longerterm ACMI provision never developed into a core product for many of these operators. Consequently, these ACMI providers have often not been able to justify higher cost, newer generation aircraft nor been able to acquire such capacity on sufficiently attractive terms.

The current trend is for the lease terms to get longer and the customer base more diversified. Nordica, for example, is increasingly able to provide newer generation ATR72-600 and CRJ900 capacity to SAS and LO T. However, the contract terms still remain much shorter than those of their large US counterparts.

In recent years, operators such as Flybe, CityJet, and Air Nostrum separately took strategic decisions to expand their respective ACMI offerings. CityJet had hitherto been a scheduled airline with a substantial presence at London City Airport, but adopted a new business model to focus on ACMI operations. This resulted in the carrier now only operating one scheduled route, while all other flights operate for major European carriers. This includes a fleet of CRJ900s that operate for SAS, RJ85s for Air France and KLM , and SSJs for Brussels Airlines. Its fleet has grown to 40 aircraft providing greater scale and a more diversified customer base than its competitors. Flybe has developed an ACMI business alongside its core scheduled offering.

Meanwhile Air Nostrum, which is known as the regional operator for Iberia under a long-standing franchise arrangement, operates with a fleet of 50 aircraft. While this agreement remains in place, it has also developed its ACMI business with customers including Lufthansa Cityline, SAS, Binter Canarias and Croatia Airlines, operating two CRJ1000s with each. Air Nostrum has already established an Irish entity, Hibernian, through which to channel future ACMI business.

New co-operation

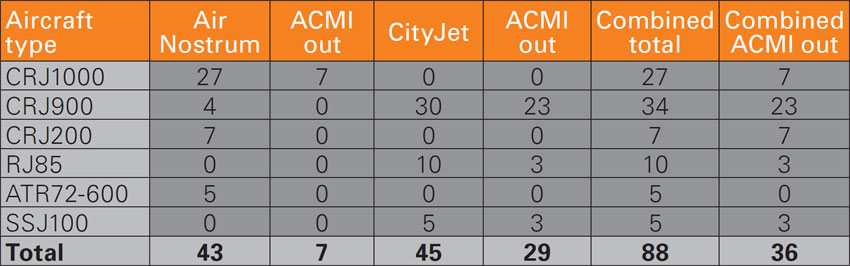

The fusion of CityJet and Air Nostrum will create the first European capacity provider that starts to approach the scale of its North American counterparts. The combined fleet of almost 100 aircraft across both carriers and those that it operates for others is shown in the chart below.

Source: ch-aviation

Source: ch-aviation

Of this fleet, 36 are flown on ACMI contracts, while the majority of the remainder flies for Iberia under a franchise. Although the structure of the combined two airlines has not yet been determined, the questions being asked are whether the new larger entity can prove that its cost structure is attractive enough to large European carriers to encourage them to outsource flying from their existing in-house operations; and if it can provide enough reassurance to major carriers that it will supply substantial capacity on a long-term basis.

With regard to cost structures, airlines can only control some levers. With no control over fuel or navigation costs and limited ability to impact maintenance charges, labour costs are the main differentiator. In particular, if the combined entity can train, pay and retain its crews at less cost than major carriers then long-term capacity agreements could become attractive to majors. This might even involve transferring their existing fleets by leasing them to the new entity, which in turn would wet-lease them back.

The other catalysts over which the combination can have some control are leasing and finance costs. A wide variety of lessors already have exposure to both airlines. In addition to TrueNoord, this includes NAC , Chorus, Falko and AeroCentury. If the combined unit also becomes a merged corporate structure this should lead to improved creditworthiness and therefore attractive finance costs.

In terms of confidence, the combined scale should give enough credibility to encourage some operators to begin considering longerterm ACMI arrangements that provide stability for both wet lessor and wet lessee. In turn, that would provide more comfort to banks and lessors like TrueNoord so that a virtuous circle may be created.

However, if there remains only one large capacity provider in Europe, there will be no effective competition. Major airlines dislike monopoly suppliers so that while it may defy conventional thinking about the benefit of monopoly power, the new conjoined carrier could benefit if a second force reached a similar scale on the European stage.

This article was published in ERA’s Regional International magazine, September – October 2018 issue.

1 October 2018